Unit 4: Methods

Table of Contents

- What are methods?

- Method Signature

- Modifiers

- Return Type

- Method Name

- Parameters

- Calling Methods

- Overloading

- JavaDocs

What are methods?

Loops allowed us to repeat sections of code. However, what happens if we want to repeat a loop? What about repeat a selection structure? We can use something called methods to group blocks of code and reuse them so that we don’t have to rewrite similar processes every time.

Methods also make your program easier to read and maintain since you can break a big problem into smaller tasks. (This is called modularity.) Methods also allow other people to use your code without needing to understand exactly how it works. For example, think about the Math.sqrt() method. We don’t really know how the square root is calculated. We just need to know what it does.

Note: In other programming languages, methods are also referred to as functions.

Method Signature

A method’s signature (aka header) contains key information about the method and is at the top of the method declaration. You have actually seen a method signature before – the main method!

public static void main(String[] args)

The general form of a method signature is as follows:

modifier(s) returnType methodName(parameterType parameterName, ...)

Let’s break down what each of these things mean.

Modifiers

Modifiers allow us to specify who can access the method and under what circumstances. There are 4 visibility modifiers in Java, which are summarized in the table below. A green checkmark indicates visibility while a red X indicates that it is not visible.

| Visibility Modifier | Class | Package | Subclass | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|

private | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| default (no modifier) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

protected | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

public | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

As you can see, private is the most restrictive modifier while public makes it available everywhere (globally).

package : the folder (aka directory) that the class is under*

subclass : a class which inherits methods and fields from a superclass (aka parent class)**

*Note that in Java, we declare that a class is inside of a package using the package keyword as the first line of code in the file. For example, if my class HelloWorld.java was under the folders learncode/src/com/omegarobotics/unit1/lessons/, I would have this at the top of the file:

package learncode.src.com.omegarobotics.unit1.lessons;

**We will learn more about classes and inheritance in Unit 5.

Note: Visibility modifiers can apply to other things in Java besides methods, such as variables and classes (which we will learn later). For example, we have been declaring all of our variables using the default modifier (no explicit modifier), which means that those variables are technically visible to the class they are declared in and other classes in the same package.

Static

static is another modifier in Java. We’ll learn more about what this really means later. For now, just accept that all of your methods will be static.

Return Type

The next part of a method signature is the return type. This is the data type that the method gives back to whoever called it. For example, when I use Math.sqrt(4), the method returns 2.0, so the return type is double.

If the method doesn’t return anything (for example, the main method), you would put void instead of a type.

When you are coding a method and you want to return a value, you use the return keyword. You can return things like variables, an expression, or a constant.

Here’s an example.

public static double cube(double x) {

return x * x * x;

}

Method Name

The method name is pretty self-explanatory. Just follow the Java identifier naming rules. By convention, methods are in camel case and are usually verbs, since they do something.

Parameters

The last part of a method signature is the parameters. Paramters are a way for you to pass data into a method in order to customize how it works. For example, I could have a method called scoopIceCream which takes 1 parameter called flavor.

Methods can have 0 or more parameters. (In the case of 0 parameters, you still need the open and close parentheses after the method name.) If you do have a parameter or two, you need to separate them with commas. You also need to specify the type and name of each parameter. Let’s look back at the previous example.

public static double cube(double x) {

return x * x * x;

}

Notice that the parameter x is of type double. Also notice that parameters are basically treated as variables that you can only use within the method body. (Once you exit the method body, the variable x no longer exists. The “region” where a variable is accessible is called its scope.)

Note: Once you hit a return statement, any code inside of the method but after the return will be skipped, similar to how break and continue work.

Parameters vs. Arguments

Note that there is a difference between parameters and arguments, even though they are often used interchangeably within the programming community. Parameters refer to the generic variables that represent some value passed into the method. The value itself is referred to as the argument.

To extend the scoop ice cream example, flavor would be the parameter, while "chocolate" or "vanilla" would be examples of arguments.

Pass by value vs. Pass by reference

Another thing to be aware of when passing arguments into a method is pass by value and pass by reference. Primitive data types are pass by value, which means essentially that a copy of the value itself is given to the method. To see this in action, see TestPassByValue.java.

Objects, on the other hand (non-primitives), are pass by reference. What does that mean?

Let’s say you have a method called squareArray which takes an array of integers. You might write the method like this:

/** Squares elements in a given array in place */

public static int[] squareArray(int[] data) {

for (int i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

data[i] = data[i] * data[i];

}

return data;

}

However, the line which returns data is superfluous because of pass by reference. Since arrays are objects, the reference to that object is passed into the method. Thus, when you do data[i] = data[i] * data[i], you are actually squaring the original values of the array. This is called updating an array in place.

Usually, you don’t want to edit the original array. In that case, you should initialize a totally separate array in order to return a separate array (see the code below).

/**

* Returns a new array which contains squared

* elements from the given array

*/

public static int[] squareArray(int[] data) {

// make a new array called result

int[] result = new int[data.length];

// fill result with squared elements from data

for (int i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

data[i] = data[i] * data[i];

}

return result;

}

Calling Methods

As mentioned previously, calling a method is the same as using the method. It usually involves writing the method name and passing any arguments the method requires. If the method returns something, you may also want to assign the result of the method call to a variable.

In the example below, we call the cube method on the argument 5, store the result in result, and then print it.

public class CallingMethods {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double result = cube(5); // call cube method

System.out.println("5^3 is " + result);

// Or do it all in one step!

// System.out.println("5^3 is " + cube(5));

}

public static double cube(double x) {

return x * x * x;

}

}

Output:

5^3 is 125.0

Note: You may be thinking, wait a second, 5 is an int, not a double! And you would be right. The way that Java gets around this is by performing automatic casting, so 5 is turned into 5.0.

Overloading

Overloading a method happens when you have multiple methods with the same name, but different parameter lists. This allows us to have flexibility in terms of what we give as arguments to a method.

For example, let’s say I want to write a method called max which returns the maximum of some numbers. First, I could start out by having 2 parameters:

/** Returns the maximum of 2 numbers */

public static double max(double n1, double n2) {

if (n1 > n2) {

return n1;

}

return n2;

}

Note: Notice that I don’t need to have an else clause because the return statement terminates the method.

But what if I want to make a max method with 3 parameters? I could do something like this:

/** Returns the maximum of 2 numbers */

public static double max(double n1, double n2) {

if (n1 > n2) {

return n1;

}

return n2;

}

/** Returns the maximum of 3 numbers */

public static double maxOfThreeNumbers(double n1, double n2, double n3) {

if (n1 > n2 && n1 > n3) {

return n1;

} else if (n2 > n1 && n2 > n3) {

return n2;

} else {

return n3;

}

}

As you might notice, it’s unwieldy to have a method with such a complicated name as maxOfThreeNumbers because what it really does is the same as the 2-parameter max method. Overloading methods allows us to get rid of that awkwardness.

/** Returns the maximum of 2 numbers */

public static double max(double n1, double n2) {

if (n1 > n2) {

return n1;

}

return n2;

}

/** Returns the maximum of 3 numbers */

public static double max(double n1, double n2, double n3) {

return max(max(n1, n2), n3);

}

Notice that there are 2 max methods with different parameter lists. This is completely valid in Java and intuitively makes sense because both return the max of some numbers.

Also notice that we can utilize the first max method in the second max method - we simply take the max of n1 and n2 (let’s call that result), and then take the max of result and n3.

Note: You can also overload methods by changing the parameter type, not just the number of parameters the method has.

Note: In real life, you wouldn’t write out a max method manually - you would just use Math.max().

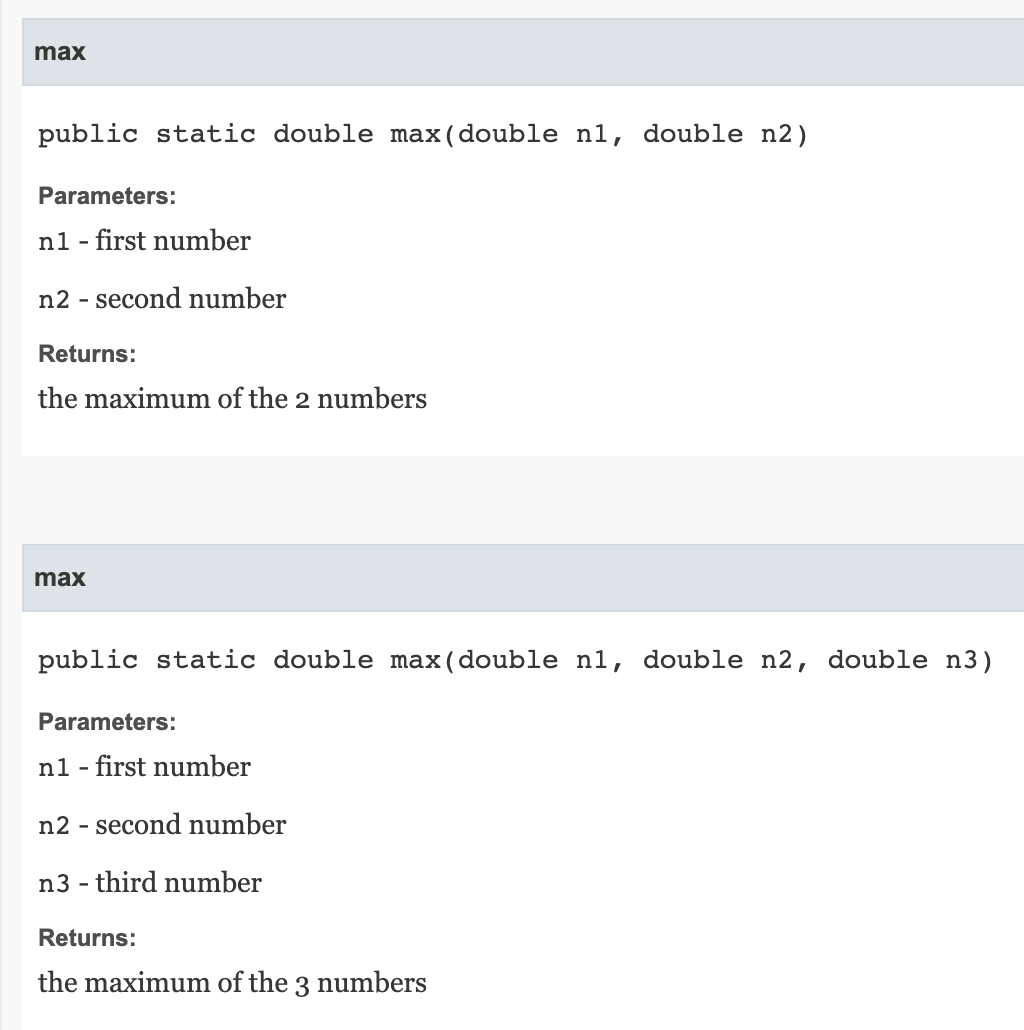

JavaDocs

You might have noticed that in the previous examples we used a special type of multi-line comment which starts with /** and ends with */. If you recall from the Comments section, that type of comment is a JavaDoc comment. JavaDoc comments are used to document sections of code, such as fields (we’ll learn about those later), classes (also later), and methods.

The cool thing about JavaDoc comments is that you can use them to auto-generate HTML documentation like this or this. You can read about how to do this on Eclipse and IntelliJ.

Learn Code also uses JavaDocs for our source code, which you can find in the javadoc directory.

Annotations

JavaDocs supports annotations to document things other than a description of the method. Here are commonly used tags:

@param- used to describe parameters@return- used to describe what is returned by the method@throws- used to describe exceptions that are thrown (see Unit 7)@deprecated- indicates that a method shouldn’t be used anymore

For a complete guide on how to write JavaDoc comments, see this article.

Here’s an example of what JavaDocs look like, from code to HTML document.

Code

/**

* @param n1 first number

* @param n2 second number

* @return the maximum of the 2 numbers

*/

public static double max(double n1, double n2) {

if (n1 > n2) {

return n1;

}

return n2;

}

/**

* @param n1 first number

* @param n2 second number

* @param n3 third number

* @return the maximum of the 3 numbers

*/

public static double max(double n1, double n2, double n3) {

return max(max(n1, n2), n3);

}

JavaDoc

Note: These JavaDoc comments are missing the method description, which you should always include.